4.3 Elasticity and Changes in Welfare

In Chapter 3, we discussed the need to measure consumer welfare in monetary terms. One of the reasons we mentioned was the ability to assess the social impact of a new technology. At this point, the reason should be clear: a technological innovation (that is, in the language of our simple mathematical model of production, a higher value of the productivity parameter $A$) leads to lower costs for firms and thus a rightward shift of the supply curve. In the new equilibrium — which lies further southeast along the demand curve — the price is lower and the quantity exchanged is higher. Consumer surplus increases: through the market mechanism, the benefits of lower costs are partially passed on to consumers.

But that’s only part of the story. What happens to producer surplus? Do firms earn higher or lower profits? The answer is not straightforward. On the one hand, firms face lower unit costs and sell a larger quantity — two effects that tend to boost profits. On the other hand, the lower selling price compresses profit margins. The final effect on producer surplus depends on the balance between these opposing forces and, as we will see, is closely linked to the concept of demand elasticity—a key idea In Chapter 5, we’ll see that demand elasticity also plays a central role in analyzing the decisions of firms with market power and in measuring that power. for understanding who gains or loses—and by how much—in response to external shocks such as technological innovations or government interventions like taxes and subsidies.

Before introducing that concept, we give an example illustrating the potentially ambiguous effect of a technological innovation on producer surplus. Assume a linear demand function: $P = 10 - Q$, where $P$ is the price per kilogram and $Q$ is the quantity in tons. Consider three supply scenarios. In the first (left graph in the figure below), supply is given by $P = 4Q$. In the second (middle graph), a technological innovation lowers marginal costs: the supply function is $P = (2/3)Q$. In the third (right graph), a further technological advance leads to the supply function $P = (1/4)Q$.

Technological progress always has a positive effect on collective welfare (total surplus). Besides confirming our intuition, this is also clear geometrically: total surplus corresponds to the area of a triangle with base equal to the intercept of the demand curve and height equal to the equilibrium quantity, which increases as the supply curve shifts to the right. The effect on consumer surplus is equally straightforward: as the equilibrium price falls, consumer surplus increases.

Producer surplus, however, behaves differently: it increases from the first to the second scenario, but decreases from the second to the third. The geometry of the graph helps explain why: producer surplus (green area) is always equal to half of consumers’ expenditure—the product of price and equilibrium quantity. So to understand how producer surplus changes, we simply need to track changes in expenditure.

In the first scenario, expenditure is $8 \times 2000 = 16000$, and producer surplus is $8000$. In the second, the price drops from 8 to 4 euros per kilo (−50%), while the quantity rises from 2 to 6 tons (+200%)—a more than proportional increase. Consumers’ expenditure rises to $4 \times 6000 = 24000$, and producer surplus to $12000$. The positive effect of increased sales (at lower cost) outweighs the negative impact of the lower price. In the third scenario, the opposite occurs: the price drops from 4 to 2 (−50%), but the quantity only increases from 6 to 8 tons (+33%). In this case, expenditure—and thus producer surplus—declines.

Elasticity of Demand

The example we just saw highlights an interesting fact: two successive technological innovations both reduce production costs, but they have opposite effects on producer surplus — the first increases it, the second reduces it.

The difference between the two scenarios depends on how the market adjusts when supply changes. If, following the shock, the quantity increases relatively more and the price decreases relatively less, producers benefit; if instead the price drops more than the quantity increases, the gain is reduced or turns into a loss.

What determines whether the adjustment will occur more through price or quantity? The answer lies in the concept of price elasticity of demand, which measures how strongly the quantity demanded of a good responds to changes in its price. Like a derivative, elasticity captures a local relationship between two variables; but unlike a derivative, it considers the ratio of percentage changes rather than absolute changes:

\(\begin{gathered} \frac{\Delta Q/Q}{\Delta P/P} \end{gathered}\)

By letting $\Delta P$, and thus $\Delta Q$, tend to zero, we obtain the elasticity of demand as a limit:

\(\begin{gathered} E^D=\frac{dQ}{dP} \times \frac{P}{Q} \end{gathered}\)

Like the derivative $dQ/dP$, elasticity is also negative and varies along the demand curve: that is, it depends on the point at which it is calculated — and, of course, on the shape of the function itself. Once the elasticity of demand has been calculated at a given point, we can distinguish two cases:

- Demand is inelastic or rigid if the elasticity is less than 1 in absolute value: $|E^D|<1$. In this case, the quantity demanded changes little in response to price.

- Demand is elastic if the elasticity is greater than 1 in absolute value: $|E^D|>1$. In this case, the quantity demanded changes more than proportionally in response to the price change that caused it.

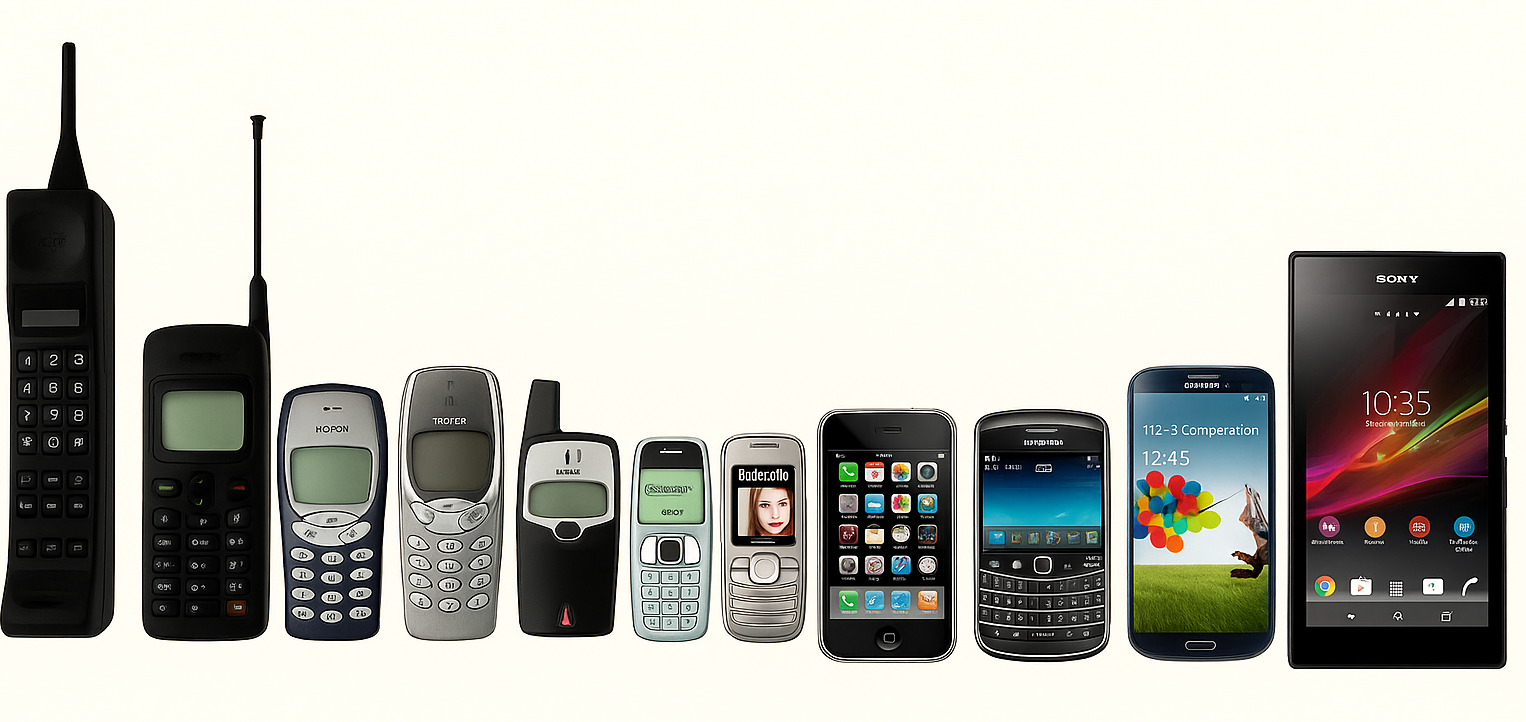

In the smartphone market of the early 2000s, demand was highly elastic. Technological progress reduced costs, sales exploded, and profits grew. The first mobile phones cost thousands of euros for very basic functions; a few years later, with just a few hundred euros one could buy a smartphone with vastly superior capabilities. Today the market is saturated and demand more inelastic: almost everyone already owns a phone, so further cost reductions push prices down but quantities increase only slightly. In fact, only the basic models have become cheaper: the average price remains high because firms focus on selling more advanced versions.

In the smartphone market of the early 2000s, demand was highly elastic. Technological progress reduced costs, sales exploded, and profits grew. The first mobile phones cost thousands of euros for very basic functions; a few years later, with just a few hundred euros one could buy a smartphone with vastly superior capabilities. Today the market is saturated and demand more inelastic: almost everyone already owns a phone, so further cost reductions push prices down but quantities increase only slightly. In fact, only the basic models have become cheaper: the average price remains high because firms focus on selling more advanced versions.

The same is true for automobiles. With the rise of mass production in the early twentieth century, demand was elastic: millions of families entered the market and profits rose. The Ford T, which initially cost more than two years of a worker’s salary, became affordable in less than a year thanks to assembly lines. Over time, however, the market became saturated and demand more inelastic.

The same is true for automobiles. With the rise of mass production in the early twentieth century, demand was elastic: millions of families entered the market and profits rose. The Ford T, which initially cost more than two years of a worker’s salary, became affordable in less than a year thanks to assembly lines. Over time, however, the market became saturated and demand more inelastic.

We can now revisit the initial example in light of the concept of elasticity. The elasticity of demand at the initial equilibrium determines whether, following a supply-side shock, the adjustment occurs mainly through price or through quantity. In the first scenario, demand was elastic: the cost reduction led to a moderate fall in price but a strong increase in sales, thereby raising consumers’ total spending and producer surplus. In the second scenario, demand was inelastic: a further cost reduction caused a sharp fall in price but only a modest increase in the quantity traded, leading to a decrease in spending and, consequently, in producer surplus.

Elasticity and Expenditure

As we have already observed, in our example producer surplus is proportional to (exactly half of) total consumer expenditure — that is, the product of price and equilibrium quantity. In fact, the elasticity of demand is directly linked to the behavior of total spending. When demand is elastic, a reduction in price leads to a more than proportional increase in quantity, and total expenditure increases. When demand is inelastic, the same price drop causes only a small increase in quantity, and expenditure decreases. At the point where elasticity is exactly equal to $1$, total expenditure reaches its maximum.

It is easy to verify these claims by looking at the derivative of expenditure with respect to price. Indeed, \(\frac{d(PQ)}{dP}=Q+P\frac{dQ}{dP}\) from which it follows that expenditure increases (i.e., $d(PQ)/dP>0$) if $|E^D|<1$, while it decreases (i.e., $d(PQ)/dP<0$) if $|E^D|>1$.

The following figure illustrates two different demand functions. In the left graph, the demand curve is given by $Q = 15/P$ (Cobb-Douglas), and in the right graph, by $Q = 10 - P$ (linear demand). For both cases, the graph calculates the elasticity of demand at each point and the corresponding consumers’ expenditure (green area).

Supply Elasticity

So far, we have focused on the elasticity of demand, which plays a crucial role when the shock affects the supply side of the market — for example, in the case of a technological innovation (or a reduction in wages, which has an equivalent effect on the market). In such cases, the supply curve shifts, and the new equilibrium is determined by moving along the demand curve, which remains unchanged: it is therefore the elasticity of demand that governs the effect on prices, quantities, and surplus.

Conversely, when the shock affects the demand side — for example, due to a change in income — it is the elasticity of supply that determines the impact on the equilibrium, because the adjustment occurs along the supply curve. As we will see in Chapter 7, in the case of public policies such as taxes or subsidies, both sides of the market are effectively affected, and the equilibrium shifts along both curves. In that case, it is the relative elasticities of demand and supply that determine who bears the burden of the tax or who benefits from the subsidy — and to what extent.

For simplicity, in these notes we have adopted two standard assumptions: short-run supply is represented by a straight line starting from the origin, and therefore has unitary elasticity; in the long run, supply is instead assumed to be perfectly elastic, a horizontal line at $AC_{\text{min}}$. These assumptions help us isolate the role of demand elasticity more clearly, which will remain the key element in the analyses presented in the following chapters. In particular, in the next chapter we will see that the elasticity of demand is central to analyzing the decisions of firms with market power and to measuring the extent of that power.